SITE DIRECTORY

To learn more about any of the BCN sites listed below, click “Read more” to view individual site briefs. To search for a specific BCN site, use the search bar below:

Promise Land Cemetery

PROMISE LAND CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1880

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

The Promise Land Community was established and settled by former slaves from the Cumberland Furnace during the Reconstruction Period (1870-1875) in Charlotte, Tennessee.

Deed records and Census reports reveal that some of the early settlers were Nathan Bowen, Joe Washington Vanleer, William Gilbert, John Grimes, Jeff Edmondson, Charles Redden, George Primm, and U.S. Colored Troop Veterans brothers, John and Arch Nesbitt, Clark Garrett, Landin Williams, and Ed Vanleer. These early settlers went on to become landowners with their descendants continuing to own the land.

The Promise Land Cemetery was established in 1880. John Nesbitt purchased property with backed pension funds. U.S. Colored Troop Veterans are buried at this site like John Nesbitt and Arch Nesbitt.

Today, only the St. John Promise Land Church and the old Promise Land School Building remain. In 2007 the Promise Land School Building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In July 2010 a Civil War Trails Marker was placed on the site of the historic school building in recognition of the Civil War records of John and Arch Nesbitt and their contributions to the community.

BCN Contact Information:

Promise Land Heritage Association

TuesRd2@gmail.com

www.promiselandtn.com

Catoctin Furnace African American Cemetery

CATOCTIN FURNACE AFRICAN AMERICAN CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1774

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S):

Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, Inc.

HISTORY:

The Catoctin Furnace African American Cemetery was rediscovered in the 1970s during preconstruction archaeological surveys for the proposed Route 15 corridor. In 1979, an archaeological data recovery excavation was undertaken and 35 graves were excavated. The human remains and associated artifacts recovered during the State Highway Administration excavations were taken to the Smithsonian Institution where they remain.

The Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, Inc. began a reanalysis of the cemetery in 2014 including heavy metals, stable isotope, and aDNA. We also compiled documentary resources to help place the study results into the context of past and present living peoples with the goal of identifying the origins of and descendants of the 18th- and 19th-century enslaved workers at Catoctin Furnace. Forensic facial reconstructions of two enslaved ironworkers are in the Museum of the Ironworker and aDNA has identified five family groups.

The Catoctin Furnace African American Cemetery may represent the most complete African American cemetery connected with early industry in the United States and may hold the key to understanding the origins of skilled African iron workers in the industry. Ultimately, results of this research will be utilized to increase awareness of the contribution of the African American workers to the iron industry at Catoctin, educating and informing the public about the role of African Americans in the industrial development of the United States.

BCN Contact Information:

Elizabeth Anderson Comer

ecomer@catoctinfurnace.org

www.catoctinfurnace.org

BARBEE-HARGRAVES CEMETERY

BARBEE-HARGRAVES CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1790

ADDITONAL NAMES: Town of Chapel Hill

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

The cemetery was in use from 1790 until 1915 for African American burials, predominantly slaves of the Morgan, Barbee, and Hargrave families and their descendants. Mark Morgan is known to have owned six slaves in 1755 named Rafe, James, Nell, Cate, Jude, and Cloe. By 1777, in the inventory of his estate, he owned 22 slaves. Since at this time slaves were inheritable property, it is likely that these enslaved laborers became property of Mark Morgan’s son Hardy. As Hardy Morgan acquired additional land grants, adding to his father’s property, he may have also acquired more slaves. The majority of the graves likely belong to these African American slaves or their descendants. There is some possibility that the cemetery was used for white burials as well.

Few of the graves are identified, but oral history tradition and interviews conducted with Hargrave descendants indicate that George Hargrove, who died in 1910, and his wife, Charlotte Hargrove, are buried in the Barbee-Hargrave cemetery. There are also stories of an engraved headstone that read “Thomas” and “1805.” It was estimated before ground penetrating radar that there were about 40 to 50 graves in the cemetery.

In May 2011, the Town of Chapel Hill Department of Parks and Recreation contracted Preservation Chapel Hill to conduct research on the cemetery and ensure its preservation. PCH worked with Scott Seibel and Terri Russ of Environmental Services, Inc., to locate and record possible unmarked grave shafts. Through the use of these methods, Seibel and Russ found that there were 53 potential burials, 24 of which had a stone marker while 29 had no observable markers. Most of the potential graves were located in noticeable rows, making them more certain.

BCN Contact Information:

Debra Lane

DLANE@TOWNOFCHAPELHILL.ORG

Eden Cemetery

EDEN CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1902

ADDITONAL NAMES: Historic Eden Cemetery

AFFILIATION(S):

Pennsylvania Hallowed Grounds

HISTORY:

The creation of the Eden Cemetery Company was a collaborative effort to provide a sanctuary in the Philadelphia area where African Americans could be buried with dignity and respect. Founded at the height of Jim Crow, six years after Plessy v. Ferguson, Eden Cemetery was Philadelphia's African American answer to a burial crisis created in the community, due to segregation, urban expansion, public works projects, vandelism, condemnation, and the closure of earlier Black burial grounds and cemeteries. Having a dignified place for burial was a long-standing challenge to African Americans due to racism, but by the end of the 19th century the situation in Philadelphia grew even more dire with the closures of Lebanon and Olive cemeteries and the enactment of municipal ordinances that in effect prohibited the creation of new African American cemeteries within City limits.

Opened in 1902, Eden represented African American agency to address these problems by establishing a new cemetery in suburban Delaware County on fifty-three acres that were part of Bartram Farm, and as a "collection cemetery" for dislocated earlier black burial grounds and cemeteries. This move was not fraught without challenges. On August 12, 1902, Collingdale's white residents blocked the entrance to the cemetery, protesting "a colored burial ground" in their community. Authorities of the borough delayed the funeral for hours. The Delaware County community protested against its opening with a court injunction. The headline in the August 13th, Chester County Times read: "Collingdale Has More Race Troubles, Town Council Has No Use for a Colored Funeral, No African Need Apply." When a compromise was finally reached, Eden was able to have its first burial on August 14, 1902.

The cemetery quickly became a beacon of community pride and representation of African American heritage through the designation of its cemetery sections. An example of this is the John Brown section, which became the chosen resting place for many United States Colored Troops and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a Citzen of Eden, who viewed John Brown as an important friend and hero.

Since its beginning, Eden has been a steward of the history and culture of a people, of communities made invisible,. A legavy cemetery, Eden is comprised of dislocated burial grounds, churchyards and cemeteries with over 90,000 persons entrusted to its care. The lives of the Citizens of Eden span from 1721 to the present. Monuments throughout the cemetery eternally memorialize the lives of many thousands, who are an important part of history, and the communities that they represent.

Historic Eden offers a unique cultural, educational, and historical resource in the Greater Philadelphia, Delaware Valley, and the Southeastern Pennsylvania area. The past, present, and future converge at Eden, reflecting a broad spectrum of American history, heritage, culture and memory. Eden offers tours and events designed to educate and connect the past with the present and the future.

Today, Eden is an exceptional monument to the national African American civil rights story. Historic Eden Cemetery is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, is a part of the National Park Service Underground Railroad to Network to Freedom, a member of the Pennsylvania Hallowed Grounds and a member of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Eden looks to the future with a continued focus on stewardship and service, with a strong consideration of how the cemetery will adapt to the ever-changing needs of the community, so that Eden can continue to preserve memory and to provide stewardship and service well into the next century.

BCN Contact Information:

Eden Cemetery

info@edencemetery.org

Cedar View Cemetery

CEDAR VIEW CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1850

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

In 1850, John B. Crawford, a local land and enslaver sold the 2.5-acre site to a group of 14 Black men for use as a cemetery. The group was comprised of free black men and former slaves.

The cemetery consists of 24 plots, each measuring 99 by 39 feet. The cemetery served as the burial ground for many African American families. There are former enslaved people as well as for Civil War USCT buried at the site.

The cemetery is not active, but it is an open area, open to the public.

BCN Contact Information:

Friends of Cedar View

friendsofcedarview@gmail.com

Oakwood Cemetery

OAKWOOD CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1839

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S):

Save Austin's Cemeteries

HISTORY:

Founded in 1839, and containing over 23,000 burials within 40 acres, Oakwood Cemetery is Austin's oldest municipal burial ground. The first interment was that of an enslaved African American man who was killed while being brought into Texas by enslavers. Early burials were in the western section of the cemetery, near the Navasota gate. When the cemetery was platted in 1866, it included the area segregated by race and socioeconomic status. The Historic Colored Grounds lie on the north side of the cemetery’s main road, appearing as a flat green space with a sparse scattering of 300 gravestones. The monuments exist in various states of disrepair, some slightly visible above the grass line, many face down, and others sinking beneath the topsoil. Records indicate that thousands of named individuals are buried within this area and subsections, but no map exists as to the exact location of the burials. Additionally, early sexton’s ledgers reveal entries of hundreds of unnamed individuals, noting only their race or enslaver’s name, further denying the opportunity for descendants to trace ancestry or burial information.

The Historic Colored Grounds hold the remains of most of the cemetery’s African American burials, both free and enslaved peoples, many of whom settled in Austin’s renowned freedom colonies after the Civil War. Among them are civil rights leaders, educators, cultural icons and religious figures influential on local, state and national scales. Some of these individuals have monuments, but most do not. The City of Austin believes that Austin’s historic cemeteries remain vital for the community to remember its segregated past and how the city has changed since its founding. The segregated grounds of Oakwood Cemetery serve as a site of, and memorial to, the ongoing advancement of civil rights, in recognition of the struggle for Black equity over the past two centuries. The individuals buried in the Historic Colored Grounds were subject to segregation and institutional racism in life and death. This is evident in the poor keeping and absence of historical records compared to the rest of the cemeteries’ burials.

BCN Contact Information:

Jennifer Chenoweth

jennifer.chenoweth@austintexas.gov

https://www.austintexas.gov/department/oakwood-cemetery-chapel

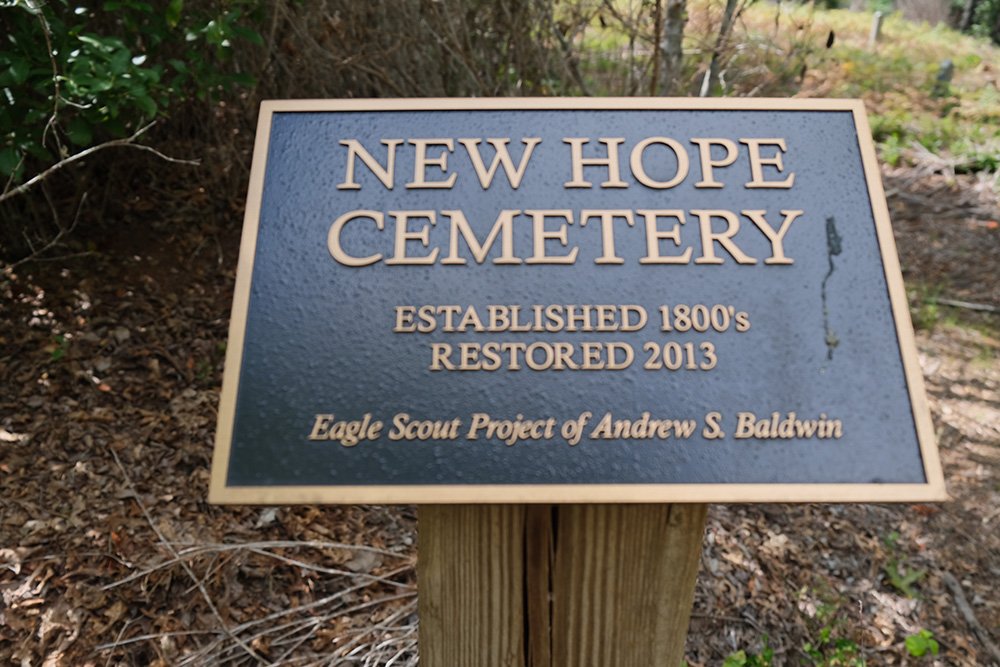

New Hope Cemetery

NEW HOPE CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1800s

ADDITONAL NAMES: New Hope Church Cemetery, New Hope Methodist Church Cemetery

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

New Hope Methodist Church was established between 1885 and 1890 by the Black congregants of Franklin United Methodist Church. According to the late Barbara McRae, a local historian, the trustees of New Hope Methodist Church officially acquired the land tract for the cemetery in 1893. However, New Hope Cemetery was likely used prior to the establishment of the church. Usage of the cemetery ceased in the 1940s, when New Hope Methodist Church membership declined, and the church fell into disrepair. The church’s building, which is no longer standing, is said to have been burned or torn down in the late 1960s. The cemetery was in a poor condition since at least 1938, when a Works Progress Administration (WPA) worker noted that the cemetery’s condition was “very bad.” The WPA survey of the cemetery notes the four headstones that were readable at the time, which included: Lizzie Dickey, Ada Greenwood, Mollie Holden, and Jency McAfee. There is a total of 7 marked and at least 34 unmarked graves in the cemetery. Death certificates from 1909 onwards verify that at least 40 individuals were buried in the cemetery.

The cemetery is located at the top of a steep hill, which overlooks land that served as a community to a number of African American families during that time period. The last known member of New Hope Methodist Church, Josephine Greenwood Burgess, recalled that the road for carrying bodies into the cemetery eventually washed out, making the last funerals and maintenance of the cemetery difficult. Ms. Josephine Burgess passed away in 2014.

The cemetery was restored by Andrew Baldwin as part of an Eagle Scout project in 2013. He presented his proposal to clean up the cemetery to the Macon County Board of Commissioners, who agreed to support his project. They declared the cemetery “public and abandoned.” Baldwin gathered a group of volunteers, including students and a faculty member from Western Carolina University. The county contracted with a company to conduct a survey of the cemetery. As a result of Baldwin’s work, a sign was placed at the cemetery in March 2013. Later that year, the Macon County Cemetery Board of Trustees was also established to oversee maintenance of New Hope Cemetery and other abandoned cemeteries in Macon County.

BCN Contact Information:

Olivia Dorsey

hey@oliviapeacock.com

Woodlawn Cemetery

WOODLAWN CEMETERY

FOUNDED: At least since 1928

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S):

NC Historic Cemetery Registry

HISTORY:

This cemetery is located in historic West Southern Pines. In 1923, West Southern Pines was one of the first incorporated Black Townships in NC. It is on a parcel contiguous to the site of the West Southern Pines Rosenwald School that was built in 1924. The Rosenwald School building is no longer in existence.

It was made available by the Buchan Family in mid-1960’s. The West Southern Pines Churches used this cemetery to bury the members of their church.

Woodlawn Cemetery is listed on the NC Historic Black Cemetery Registry file #31MR446.

BCN Contact Information:

Southern Pines Land & Housing Trust

info@splandandhousingtrust.org

Strieby congregational United Church of Christ cemetery

STRIEBY CONGREGATIONAL UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1880

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

Strieby was founded by the Rev Islay Walden, who was visually impaired, grew up enslaved in the community. After emancipation, he received his teaching degree from Howard University in 1876, during which time he wrote his fist book of poems, “Miscellaneous Poems, Which the Author Desires to Dedicate to the Cause of Education and Humanity” and founded a Sabbath School. Subsequently he attended and graduated from the New Brunswick Theological Seminary, where he wrote a second book of poems, “Walden’s Sacred Poems with a Sketch of His Life,” and established another school called the Student Mission. He was ordained in 1879 and returned to Randolph County, NC, under the auspices of the American Missionary Association. He purchased 6 acres in southwestern Randolph on which he built both a church and a school and the cemetery, first called Promised Land Church and Academy. The school and church became important centers of African American life. In 1883, Walden petitioned for and was appointed postmaster of a community post office, named Strieby. The church, school, and cemetery were subsequently renamed Strieby. The school continued until the late 1920s when it was merged with another county African American school. A new church building was built in 1972 after the original was condemned. Descendants of the founders continue to bury family members in the cemetery. Rev. Islay Walden died in 1884 and is buried in the cemetery. Vella Lassiter, a community member, graduate of the school, teacher, and trustee, who won a landmark civil rights case in 1937 and affirmed by the state Supreme Court in 1939, is also buried in the cemetery.

In 2014, the site was named a Randolph County Cultural Heritage Site, by the county Historic Preservation and Landmark Commission. In 2021, the site was named a Literary Landmark by United for Libraries, in honor of the the Rev. Islay Walden, “Blind Poet of North Carolina.”

BCN Contact Information:

Margo Lee Williams

margolw@gmail.com

Harold Avenue Cemetery

HAROLD AVENUE CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1808

ADDITONAL NAMES: Jackson Cemetery

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

The Harold Avenue Cemetery, circa 1808, is also known as the Black Jackson Cemetery. Located west of Old Mill Road between Lawrence Place and Harold Avenue in Wantagh is a wooded area that was used as a cemetery. The Harold Avenue burial lot was used by the descendants of the Jackson family slaves prior to 1862, the date of the first recorded burial in the Old Burial Ground on Oakfield Avenue in Wantagh.

Thomas Jackson, a white Revolutionary War veteran, deeded the property to Jeffrey Jackson, who was black, in 1808. It is probable that Jeffrey Jackson was a freed slave.

Slavery in this area had lost favor soon after the Revolutionary War and was not generally practiced. Many of the area's white families were Quakers and were opposed to slavery. The former slave owners often gave land to their freed slaves for their own farms. In many cases, the grateful freed slaves took the surnames of their former masters.

BCN Contact Information:

The Wantagh Preservation Society

wantaghmuseum@gmail.com

516-826-8767

https://nyheritage.org/organizations/wantagh-preservation-society

Woodlawn Cemetery

WOODLAWN CEMETERY

FOUNDED: May 13,1895

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

Woodlawn Cemetery is a historic cemetery in the Benning Ridge neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. The 22.5-acre (91,000 m2) cemetery contains approximately 36,000 burials, nearly all of them African Americans. The cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 20, 1996.Woodlawn Cemetery was founded because of a crisis among the black burying grounds. Graceland Cemetery, founded in 1871 on the edge of the Federal City, was rapidly engulfed by residential development. By the early 1890s, the decomposition of bodies in the partially filled cemetery was polluting the nearby water supply and creating a health hazard. The Commissioners of the District of Columbia (the city's government) pressed for the closure of Graceland to accommodate the need for housing. With Graceland on the verge of closing, a number of white citizens decided that a new burial ground, much farther from any development, was needed. A portion of which was the site of the American Civil War's Fort Chaplin Burial plots were quickly laid out, and Woodlawn Cemetery opened on May 13, 1895. Between May 14, 1895, and October 7, 1898, nearly 6,000 sets of remains were transferred from Graceland Cemetery to several mass graves at Woodlawn Cemetery. Over the years, the closure of smaller churchyard cemeteries in the Federal City as well as some large burying grounds resulted in more mass graves. The last major transfer occurred from 1939 to 1940, when 139 full and partial sets of remains were relocated to Woodlawn. In all a dozen mass graves eventually came to exist at Woodlawn Cemetery. Woodlawn was an integrated cemetery, in that it accepted burials of both whites and blacks. Internally, however, it was segregated, with Caucasians being buried in a whites-only section.

As the cemetery filled and space for burial became available in desegregated cemeteries, income from the sale of burial plots dropped significantly. White burials at Woodlawn, once a significant source of income, plummeted after 1912. Lacking a perpetual care trust, the cemetery fell into disrepair. The last burial was made there about 1969,with the total number of dead at the cemetery about 36,000.

The Washington DC Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. has had a relationship with Woodlawn Cemetery since 2018, when we discovered that one of our Founders, Mary Edna Brown Coleman, was buried there. We had a vested interest in the preservation of the cemetery. In 2022, we discovered that there were two Founders of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., Marjorie Hill and Sarah Merriwether Nutter, also buried at Woodlawn, so we invited Xi Omega Chapter of AKA to join us in collaboration, in assuring that the sacred grounds of Woodlawn Cemetery would always exist.

It is our desire to build community awareness of the many needs of the cemetery, while assisting the volunteers with tasks identified. Our organizations, therefore formed the Woodlawn Collaborative Project to make a difference in this sacred burial space of our ancestors.

BCN Contact Information:

Tamara Phelps

granddeltadime@gmail.com

Woodland Cemetery

WOODLAWN CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1917

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

Opened in 1917, during the Jim Crow era in the capital of the confederacy, Woodland's roads and front gate were built by local African American contractors. In 1916 when the cemetery was under construction, the pond was still in use as indicated by the newspaper advertisement. Families would picnic by the pond and paddle boat in it. Mitchell’s desire was to create a dignified and respectful place for African American families to come and pay homage to their deceased family members. Mitchel named the roads at Woodland after African American heroes of that era as a counter to the erection of the confederate statues on Monument Ave. Not only are the elite of Richmond’s black community buried here but Woodland has served as a dignified resting place for our US veterans of the Spanish-American War, World War I and II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Woodland Cemetery is a testament to the perseverance, dignity, and the desires of the African American community to be respected. John Mitchell was acutely aware of these feelings and his vision provided a way for respect to be shown with pride.

The significance of this cemetery is that it is evidence of a history that will be lost if we do not preserve it. Our children will grow up ignorant of the accomplishments and contributions of a whole segment of people who greatly contributed to the development of the City of Richmond. Considering the criticism and removal of African American history from our schools, Woodland will be a counter to an unbalanced history that is taught today by referencing the true history of the struggles and accomplishments of African Americans. Without Woodland’s historical contribution our children will not only grow up unaware of their history and leaving many to feel insignificant and marginalized.

BCN Contact Information:

Marvin Harris

mharris@mapinv.com

African Union Church Cemetery

AFRICAN UNION CHURCH CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1835

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

Property bought in 1835 by five Black residents of Polktown, the adjacent free Black hamlet: site of original small church. Polktown was one of the earliest free Black settlements in Delaware. The church later moved into Polktown proper. At least Five United States Colored Troops veterans are buried here, and a handful of other markers remain. The restored cemetery and memorial plaza come at the end of two decades of work and research. See www.africanunioncemetery.org and Facebook.

BCN Contact Information:

Friends of the AUCC

africanunioncemetery@gmail.com

Spring Valley AME Church and cemetery

SPRING VALLEY AME CHURCH AND CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1880

ADDITONAL NAMES: N/A

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

Spring Valley AME is a small church once affiliated with Mother Bethel AME. Located in Concord Ville (Glen Mills) Delaware County PA. The exterior has been renovated & a grave marker placed for those buried there. The AME Church is listed on the Concord Township Historic Resources Inventory as Resource #132, and as such is covered under the Concord Township Historic Preservation Ordinance. The church is a Class 2, meaning it is historically significant to the local history, being the only black church in the township.

Well-known African American Concord Ville soldier and patriot, James T. Byrd, born March 10, 1905 and passed away on May 8, 1985, was a member of Spring Valley AME Church. He is buried in what was called the “colored people’s” cemetery. James Byrd was the father of Betty Byrd Smith (a civil rights activist) and Thomas Byrd.

BCN Contact Information:

Concord Township Historical Society

https://concordhist.org/about-the-society/

610-459-8556

Clark Family Cemetery

Clark Family Cemetery

FOUNDED: 1830s

AFFILIATION(S): N/A

HISTORY:

In the 1790s, soon after Vermont became a state, a Black family originally enslaved in Connecticut, migrated to northern Vermont. Shubael and Violet Clark chose a rural hill in Hinesburgh with good loamy soil to farm, which the family did for three generations. They were successful, becoming members of the Baptist Church, attending local schools, and voting in town elections. The farm was sold off in pieces after the Civil War, as soldiers from this family returned home from the war. They no longer wished to farm the hill country and moved down into the Champlain Valley to continue farming. One soldier, Loudon Langley, stayed in South Carolina and became a founding father of Radical Reconstruction. He is buried in the National Cemetery in Beaufort, SC but his ancestors are in the Clark Cemetery. We have found no other Black cemetery in VT.

BCN Contact Information:

Elise A. Guyette

eguy949@gmail.com

Webber Cemetery

WEBBER CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1856

ADDITONAL NAMES: Webber Family Preservation Project

AFFILIATION(S):

Webber Family Preservation Project

HISTORY:

John Webber & Silvia Hector-Webber were Texas settlers who established current day Webberville in Travis County Texas. John was an Anglo from Vermont and Silvia was born enslaved in Spanish territory Florida current day Louisiana. John Webber met Silvia while she was enslaved by another Anglo Texas settler John Crier. John Webber began a relationship with Silvia, and they conceived 3 children before being able to obtain their freedom from John Crier in 1834. John and Silvia were married by Father Michael Muldoon and established a home together on the Colorado River. They raised 10 children in their settlement before being forced to flee due to threats by intolerant new settlers.

They purchased land on the Rio Grande River border in Hidalgo County Texas and on the Mexico side in current day Tamaulipas in 1854. At their ranch “Webber Rancho Veijo” they owned and operated a ferry which they used to aid enslaved peoples in their fight for freedom into Mexico where slavery had been abolished. During the civil war John and 3 of their sons were arrested by the confederate army as Union sympathizers. After the Civil war they resided in Mexico until 1880 before returning to their Ranch in Texas. John Webber died on July 19, 1882 and Silvia remained on the Webber Ranch till her death on September 13, 1892. They are buried in the cemetery still present and open where their ranch once stood. It was recently approved for an undertold history marker through the Texas Historical Commission, for their part in the Underground Railroad into Mexico.

BCN Contact Information:

Leslie Trevino

wfpptx@gmail.com

Macedonia Baptist Church Cemetery

MACEDONIA BAPTIST CHURCH CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1968

ADDITONAL NAMES: James Thomas Howard

AFFILIATION(S): None

HISTORY:

First church erected by former enslaved families in Hillsdale/Barry Farm, a new African American settlement established by the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1867 to help relieve the housing problem encountered by black refugees who had arrived in Washington in droves during the Civil War. The idea for the settlement grew out of a meeting between General O.O. Howard, commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and a group of African American refugees living in a makeshift settlement on K Street between 14th and 17th Streets. Howard told the group that they could not stay on land that was not theirs. They responded “very pertinently,” according to Howard’s autobiography, “‘Where shall we go, and what shall we do?’” Howard replied with a question of his own: “What would make you self-supporting?” and heard an almost unanimous answer: “Land! Give us Land!”

The Freedmen’s Bureau responded by creating a settlement for newly arrived African Americans, offering to sell them lots and enough lumber to build a small house. In April 1867 the agency spent $52,000 to buy 375 acres of farmland from the Barry family (former slave owners) on the eastern bank of the Eastern Branch, as the Anacostia River was then known. The land was quickly surveyed into one-acre lots that “were taken with avidity,” Howard noted, because the prospect of owning land was an excellent stimulus for the newly freed African Americans. “Everyone who visited the Barry Farm and saw the new hopefulness with which most of the dwellers there were inspired,” Howard recalled, “could not fail to regard the entire enterprise as judicious and beneficent.”

Macedonia was quickly built on one of the first plots purchased.

BCN Contact Information:

Trish Savage

tsavage2737@comcast.net

Mount Peace Cemetery

MOUNT PEACE CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1900

ADDITONAL NAMES: Mount Peace Cemetery Association

AFFILIATION(S): None

HISTORY:

Established in 1900, Mount Peace Cemetery is a historic African American community burial place located in Lawnside, Camden County, NJ. No longer an active burying ground, Mount Peace is the final resting place of 7,000 people, including freedom seekers, 135 United States Colored Troop Civil War veterans, and Reverend Alexander Heritage Newton, whose 1917 autobiography, Out of the Briars describes his assistance to freedom seeker H.E. Bryan on his journey from New Bern, North Carolina.

A non-sectarian cemetery, Mount Peace served the African American population of Camden County, New Jersey from 1900 until 2010. Today it is maintained by the Mount Peace Cemetery Association. Mount Peace Cemetery is located in a historically African American enclave with roots into the early 19th Century and is significant to the Underground Railroad. Nineteenth century references to this unincorporated community called it Free Haven and Snow Hill. This was a place of settlement of freedom seekers in these early years. By the 1830s an AME Church was established there. The area was formally incorporated as Lawnside in 1907. The Mount Peace Cemetery and Funeral Directing Company was established in 1900 to provide the African American population of the City of Camden, New Jersey and surrounding communities appropriate and respectful burial of their dead.

BCN Contact Information:

Dolly Marshall

contact@mtpeacecemeteryassociation.org

Lebanon Cemetery (York, PA)

LEBANON CEMETERY

FOUNDED: 1872

ADDITONAL NAMES: None

AFFILIATION(S):

Pennsylvania Hallowed Grounds

HISTORY:

Founded in 1872, Historic Lebanon Cemetery in York, PA was established when the African American citizens in the area came together to purchase almost 2 acres of land to bury their families with dignity and respect. Segregated burial practices existed at the time (and continued through the 1960s), leaving the only other option for burial the “Potter’s Field”, which was overcrowded and preyed upon by grave robbers. The original 2 acres eventually grew to 5 acres over years. The cemetery reflects the diverse historical development of York; former enslaved have been laid to rest among freedmen and women and the Civil War soldiers who fought for their freedom, and men and women transcend the social barriers of life to coexist in death.

Lebanon Cemetery may be York County’s largest and oldest Black-owned cemetery.

BCN Contact Information:

Samantha L. Dorm

sdorm@friendsoflebanoncemetery.com

Mount Holly Colored Cemetery

MOUNT HOLLY COLORED CEMETERY

FOUNDED: Oldest identified burial 1888

ADDITONAL NAMES: None

AFFILIATION(S): None

HISTORY:

The Mount Holly Colored Cemetery is on Cedar Street near Mountain Street in Mount Holly Springs, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. During and after the Civil War, people coming north from southern states stopped in Mount Holly Springs and stayed to take the jobs in the town’s paper mills, establishing the Mountain Street community. The cemetery was the burial ground for all the black residents of Mount Holly Springs since they were not permitted to be interred in the town’s municipal cemetery.

Over time the community changed. By 1970 Mount Tabor AME, a small frame church (ca 1870) across the road, was abandoned and crumbling and the cemetery neglected and overgrown. The Mount Tabor Preservation Project was formed in 2019 to repair and preserve the site. GPR scans indicate the grounds included approximately 65 burials, although only 18 headstones exist. There are seven USCT Civil War veterans who were formerly enslaved.

BCN Contact Information:

Mount Tabor Preservation Project

mttaborpreservation@gmail.com